They could never tear us apart – an update on separate determinations

Often, parties will try to break off pieces of their dispute and ask Courts to determine those pieces early. It is up to the judge whether the case will be split into pieces or whether everything is determined at trial (the default position).

A recent decision in the Supreme Court of Queensland (Onza Industries Pty Ltd v Tingalpa Tyre & Mechanical Pty Ltd [2020] QSC 244) highlights the circumstances in which a Court will be hesitant to grant an order for the determination of separate questions in a proceeding. Parties wishing to have certain questions in their dispute determined separately should be certain that it is just and convenient to do so and that a split-trial will not result in unnecessary duplication or prolongation of the proceeding.

Why would anyone want to cleave off part of their dispute?

It can be good litigation strategy to do so. For example:

- You want to determine an important "threshold" question that will either end the dispute or substantially narrow the issues.

- There is a key issue that, if you win it, would encourage the other side to settle or concede.

- You and the other side agree that certain issues should be decided first to see if a trial is necessary.

Am I automatically entitled to cleave off the dispute?

Generally not. In Queensland you must apply to the Court with your proposed questions and the judge must agree that there are good reasons to decide those questions separately (Rule 483(1) of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999 (Qld)).

When will the Court allow a separate/preliminary question?

Onza is a useful, current case because the Judge described it as a "prime example" of when a Court should not cleave off separate questions.

The Judge called the case "complex and messy", but a key part of the dispute was whether property was bought by a company as trustee or in its personal capacity. Broadly, the plaintiff asked the Court to decide separately:

- whether the property was bought on trust (and should, therefore, go to the new trustee); and

- whether the defendant should pay it money for renting out the property and damages or compensation for certain other failings.

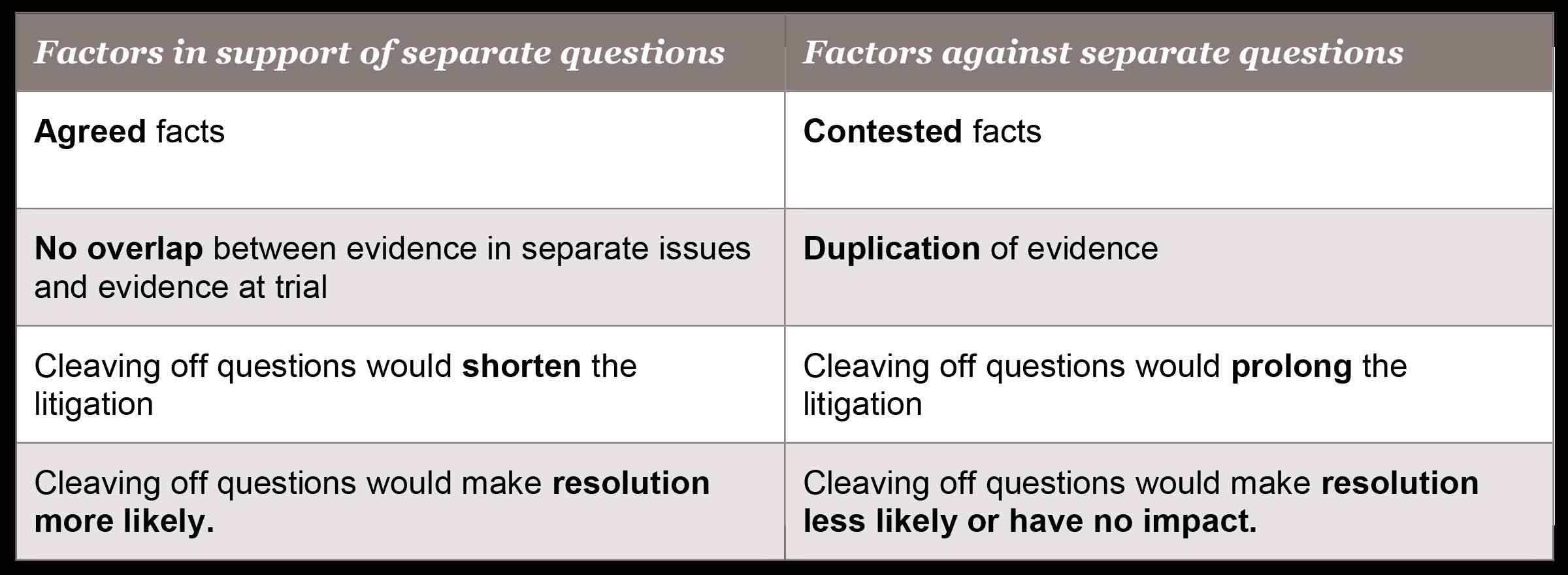

From Onza and cases to which it refers, the following are some of the good and not so good reasons to request separate questions:

Applying those principles to the Onza matter, the Judge said that it would not be just or convenient to order the separate determination. In particular, she noted that:

- the matter is complex and messy, exacerbated by the lack of legal representation for one of the parties;

- there are significant factual disputes in the matter which will require witness evidence; and

- hearing the questions separately would likely result in duplication of evidence.

The disadvantages of losing an application for separate questions include:

- the time and cost thrown away in seeking the order;

- the loss of momentum in the proceedings which may lead the party to question their prospects; and

- you may be ordered to pay the other party's costs of going to Court for the application even if you ultimately win the litigation (though the Judge did not award costs in Onza).

Key takeaways

Although the Court's discretion to order that questions be determined separately is wide, the Court needs to be persuaded that it is just and convenient to do so. Before applying for such orders, you should carefully consider:

- What strategic advantage would I gain from having a separate question decided?

- Does my case meet most of the factors above?

- What is my strategy if I cannot get the question determined separately?

Get in touch