Sweet little lies: Heinz fined $2.25m for misleading claims on Little Kids Shredz packaging

Product development and marketing review processes should encourage careful consideration of the accuracy of any product claims, including claims that may be implied from product packaging.

Last week's Federal Court order that Heinz pay a $2.25 million penalty for breaches of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) in relation to its Little Kids range of Shredz products is a reminder to businesses to carefully consider claims made on packaging, including implied claims, to avoid breaching the ACL.

What was the Heinz case about?

In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v H.J. Heinz Company Australia Limited [2018] FCA 360, the ACCC pursued Heinz for breaches of the ACL in relation to its Heinz Little Kids range of Shredz products, aimed at children aged 1 to 3 years.

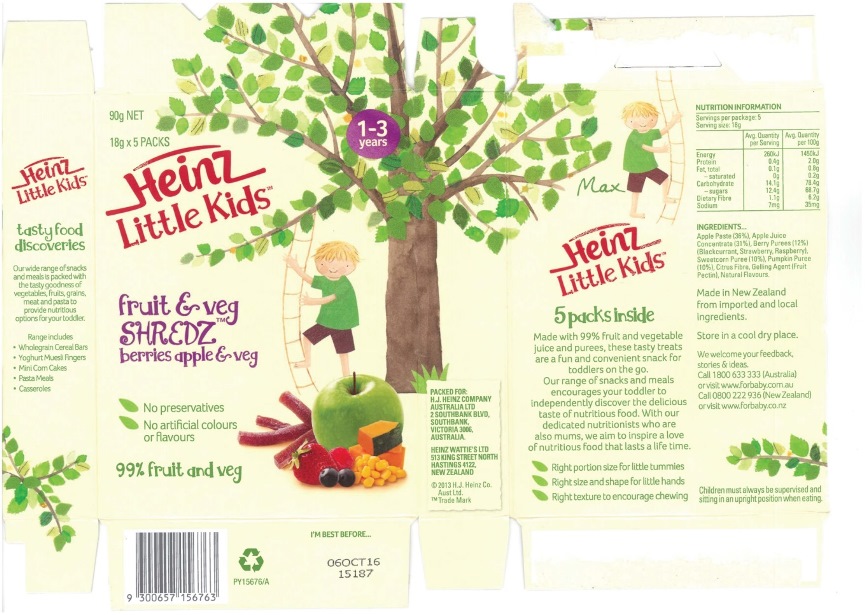

The ACCC's case was about three products in the Shredz range. The packaging for the "berries apple & veg" Shredz is shown below.

The packaging for each of type of Shredz included, as required by the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code, nutritional information which showed that the products were each approximately two-thirds sugar.

The ACCC alleged that the Shredz packaging represented that the products:

- had an equivalent nutritional value to the natural fruit and vegetables depicted on the packaging (the Nutritional Value Representation). The ACCC alleged that this representation was made by implication from the prominent photograph of fruit and vegetables, the location of the fruit and vegetables next to the picture of the Shredz, and the proximity of the fruit and vegetables and the Shredz to the words "99% fruit and veg";

- were a nutritious food and beneficial to the health of children aged 1 to 3 years (the Healthy Food Representation). The ACCC alleged that this representation was made by the packaging as a whole and, in particular, by the use of words such as "nutritious"; and

- encouraged the development of healthy eating habits for children aged 1-3 years (the Healthy Habits Representation). The ACCC alleged that this representation arose from the totality of the packaging and the statement on the box that "we aim to inspire a love of nutritious food that lasts a lifetime".

Heinz's Nutritional Value and Healthy Habits representations

The ACCC was unsuccessful in persuading the Federal Court that the Nutritional Value Representation and the Healthy Habits Representation were made by Heinz.

The Court found that the Nutritional Value Representation was not made because, contrary to the ACCC's allegations, the reference to "99% fruit and veg" was a representation about the ingredients of the product – and not a representation that the product was the same as, or as good as, the fruit and vegetables depicted on the packaging. The Court noted that consumers understand that the processing of multiple ingredients will change those ingredients and would not expect that, despite the processing, the nutritional equivalence would be preserved.

The Court found that the Healthy Habits Representation was not made because ordinary reasonable consumers would understand the phrase "we aim to inspire a love of nutritious food that lasts a life time" to be aspirational and would not think that a "representation was being made that consumption of one processed product would encourage the development of healthy eating habits".

Heinz's Healthy Food Representation

The ACCC was, however, successful in relation to the Healthy Food Representation.

The Court had "no difficulty" in concluding, based on the combination of words and imagery on the packaging, that Heinz made the Healthy Food Representation. It also found that two internal Heinz documents, a comms briefing and a brand refresh update document, supported the inference that Heinz's general intention was to promote Shredz as nutritious and healthy.

Having concluded that Heinz made the Healthy Food Representation, the next question for the Court to consider was whether that representation was misleading.

The Court broke the representation down into two separate limbs:

- Shredz were a nutritious food; and

- Shredz were beneficial to the health of toddlers.

The Court found that the first limb was not false or misleading because the products had some of the nutrients necessary to sustain human life. However, the Court held that the second limb was false or misleading because the high levels of sugars in Shredz are not beneficial to the health of toddlers, having regard to dietary considerations (including World Health Organisation Guidelines) and sugar's potential to cause dental cavities.

Dr Rosemary Stanton, one of the ACCC's expert witnesses, gave evidence that a single serve of Shredz contained the equivalent of just under three teaspoons of free sugars. Free sugars are sugars added to foods by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, including those contained in honey, syrups, fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates. Dr Stanton gave evidence that the free sugar content of the Shredz products was equal to half of the recommended daily intake of energy from free sugars for 1-2 year olds and 35% for 3 year olds. Dr Stanton noted that a single serve of any product contributing so much of the recommended levels of free sugars could not be regarded as a healthy food.

The Court also considered whether Heinz's nutritionists should have known that the second limb of the Healthy Food Representation (that Shredz were beneficial to the health of toddlers) was misleading. There were a number of internal Heinz documents in evidence which contained guidance and criteria for Heinz's toddler food products. These documents stated (variously) that:

- sugar is a "public health concern";

- dietary guidelines recommended that toddlers should consume only moderate amounts of sugars and foods containing sugars;

- products should aim to limit use of concentrated fruit juices and pastes; and

- Heinz aims for less than 30% of total sugars for a sweet snack.

Having regard to their training and experience as nutritionists, the Court found that the Heinz nutritionists ought to have known it was misleading to represent that a product containing approximately two-thirds sugar was beneficial to the health of toddlers.

What the Court ordered Heinz to pay – and do

The $2.25 million penalty imposed by the Court was significantly less than the $10 million penalty sought by the ACCC – but much greater than the $400,000 that Heinz argued was appropriate (this apparently reflected Heinz's profits from the sale of Shredz).

In addition to the $2.25 million penalty, the Court ordered Heinz to:

- establish and maintain a consumer law compliance program for three years; and

- pay the ACCC's costs of the proceeding.

The ACCC had also sought an order for corrective advertising. In refusing this order, the Court noted that Heinz stopped marketing the products shortly after the ACCC issued proceedings in 2016 and that the proceedings had attracted media attention (which had achieved some of the purposes of corrective orders).

Takeaways for businesses making product claims

In order to minimise the risk of contravening the ACL, businesses should:

- ensure that their product development and marketing review processes encourage careful consideration of the accuracy of any product claims, including claims that may be implied from product packaging;

- ensure that, where products are marketed to a specific group of consumers (eg. toddlers), claims are tested and assessed having regard to any specific guidelines relating to that group of consumers (for example, in this case, the World Health Organisation Guidelines and Heinz's internal guidelines);

- not assume that the presence of nutrients and ingredient information, as required by the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code, will "cure" any false representations about the "healthiness" or other characteristics of the product. The presence of nutritional information showing that Shredz were two-thirds sugar did not affect the Court's finding that Heinz had contravened the ACL – the Court considered it unlikely that ordinary reasonable consumers would look at the nutrients and ingredients panel when purchasing. This is another reminder that fine print cannot counteract the dominant marketing message; and

- ensure that they have a robust and appropriate consumer law compliance program, which includes regular training about the ACL.

Thanks to Julia Gillies for her help in preparing this article.