High Court confirms no royalty withholding tax and no diverted profits tax in PepsiCo

The High Court has dismissed the Commissioner of Taxation’s six appeals in the PepsiCo litigation, finding that payments by the Australian bottler for concentrate were not royalties “paid to” or “derived by” the US licensors, and the Commissioner’s DPT case failed for want of a reasonable alternative postulate.

In a narrow 4-3 majority, the High Court (Gordon, Edelman, Steward, Gleeson JJ; Gageler CJ, Jagot and Beech-Jones JJ dissenting) has dismissed all six of the Commissioner’s appeals in the PepsiCo litigation, leaving intact the Full Federal Court’s outcome for the taxpayers on both issues in dispute: royalty withholding tax (RWT) and diverted profits tax (DPT). This decision sits atop a procedural path we wrote about when the Full Federal Court handed down its reasons in the decision below in June 2024.

Relevant legal principles

Royalty withholding tax

“Royalty” within section 6(1) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (the 1936 Act) is a functional definition, and does not depend on any labels given to a payment by parties to a commercial agreement. An amount can constitute a royalty to the extent it is paid or credited as consideration for the use of, or right to use, specified kinds of IP (including trade marks).

If a non-resident derives income that consists of a royalty that is paid to it by an Australian resident, RWT is imposed on the resident taxpayer pursuant to section 128B of the 1936 Act.

Diverted profits tax

The DPT provisions, introduced to the 1936 Act in 2017, target arrangements by global entities that have the effect of diverting profits from Australia. Liability turns on whether, in connection with a scheme, a taxpayer obtained a DPT tax benefit and it would be concluded (objectively) that a person who entered into or carried out the scheme did so for a principal purpose of obtaining that benefit or reducing foreign tax.

A key feature is the requirement to test the scheme against a “reasonable alternative postulate” – a counterfactual that might reasonably be expected to have happened instead.

Background

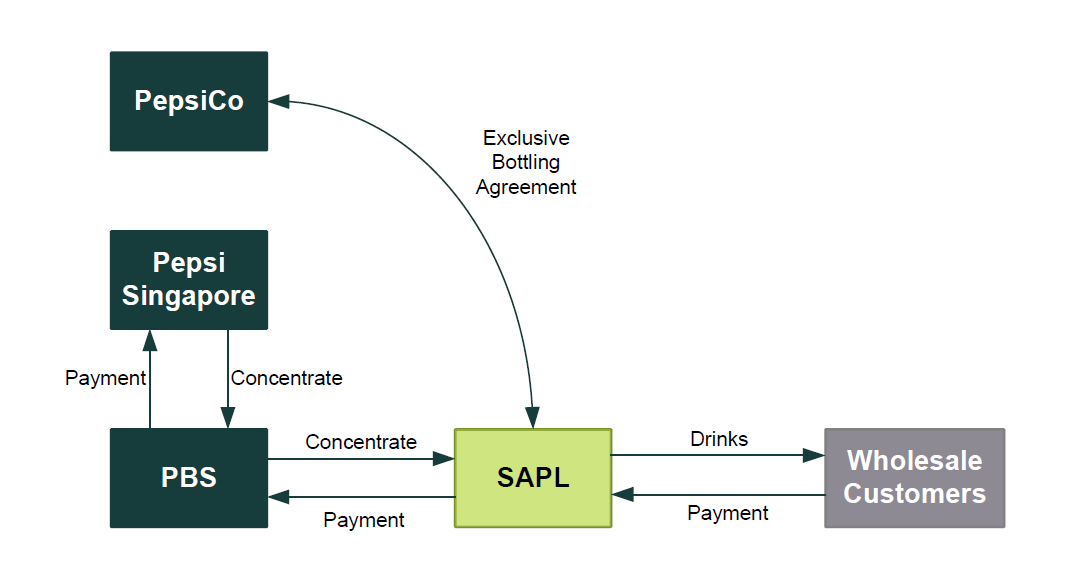

PepsiCo, Inc andcStokely-Van Camp, Inc (SVC), both US-resident companies, each entered an Exclusive Bottling Agreement (EBA) appointing Schweppes Australia Pty Ltd (SAPL) as exclusive Australian bottler and distributor of certain beverages.

Under the EBA, PepsiCo/SVC licensed SAPL the necessary trademarks and related intellectual property that enabled SAPL to make and sell the branded beverages to its customers in Australia. Importantly, no payment was required to be made by SAPL for the use of the relevant trademarks and intellectual property. The EBAs contemplated that PepsiCo/SVC would sell or cause to be sold the concentrate needed to manufacture the drinks. In practice, PepsiCo/SVC never sold the concentrate directly to SAPL.

Rather, PepsiCo/SVC nominated PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd (PBS) – a PepsiCo subsidiary incorporated in Australia – as the supplier of concentrate. SAPL had a separate sale of goods contract with PBS, and PBS earned only a thin distribution margin of approximately 0.05%, having itself purchased the concentrate from a Singaporean manufacturer.

The Commissioner contended that the concentrate payments paid by SAPL to PBS contained an embedded royalty component paid for the use of PepsiCo's/SVC's intellectual property. As a result, the Commissioner issued PepsiCo/SVC with RWT determinations and DPT assessments.

In response to the RWT determinations and DPT assessments, PepsiCo/SVC initiated proceedings in the Federal Court to have these assessments overturned. Ultimately, the Court was required to decide:

whether any part of the concentrate payments constituted consideration for the use of intellectual property (ie. an embedded or implied royalty) that was income derived by a non-resident (ie. PepsiCo/SVC), and thus subject to RWT; and

if RWT did not apply, whether PepsiCo/SVC had obtained a "tax benefit" (ie., avoiding RWT) under a scheme (ie., the EBAs and sale of goods contracts) and whether achieving this was one of their "principal purposes" in entering into and executing the relevant agreements, which would render PepsiCo/SVC liable for DPT.

It is worth noting that the Commissioner did not pursue alternative assessments based on arm's length transfer pricing principles. This is likely because the parties to the EBAs were unrelated entities and it would have been difficult for the Commissioner to convince a Court that the parties were not acting at arm's length unless there was clearly some other genuine underlying commercial transaction occurring that was separate from the sale of concentrate.

Procedural history

At first instance, Justice Moshinsky found that SAPL’s payments for concentrate included a royalty by reference to several factors in the parties’ dealings and relationship, in particular the criticality of the PepsiCo/SVC IP to the overall business context. Justice Moshinsky further concluded that if RWT did not apply, DPT would have applied instead.

On appeal, the Full Federal Court overturned Justice Moshinsky’s decision, finding that no embedded or implied royalty formed part of the price paid by SAPL for the concentrate, and that the Commissioner’s alternative postulates for DPT were not reasonable alternatives to the actual scheme.

The High Court appeal

The same three questions that framed the Full Federal Court appeal also guided the High Court’s inquiry:

Did SAPL’s payments for concentrate include an embedded or implied “royalty”?

If so, was any such amount paid or credited to, or derived by PepsiCo/SVC such that RWT ought to have been paid?

If not, did PepsiCo/SVC nonetheless become liable to DPT because, in substance, the scheme was entered into for a principal purpose of avoiding RWT and where PepsiCo/SVC either would have, or might reasonably be expected to have, been liable for RWT if the scheme had not been entered into?

Implied royalties and royalty withholding tax

On the first question, the majority took the technical view that whether a royalty existed turned on whether SAPL's payments for the concentrate was "consideration for" the IP licences. Their Honours found that "consideration" refers to "the money or value passing that moves the conveyance or transfer", adopting the approach taken by the Full Federal Court.

Their Honours subsequently found that, both in practice and according to the terms of the relevant contracts, the only basis of the payments made by SAPL to PBS was for the movement of concentrate, and not for the granting of IP licences by PepsiCo/SVC. Rather, under the EBAs, the movement of the IP licences could be attributed to a "complex exchange" of separate non-monetary undertakings that saw value flow back to PepsiCo/SVC from SAPL in the form of brand protection and exposure in Australia.

In so doing, the majority confirmed that the cases of Dick Smith and Lend Lease could be distinguished, insofar as those cases concerned "agreements where multiple promises for the payment of money or for the performance of obligations constituted, in aggregate, the consideration." In PepsiCo/SVC's case, the majority considered that there were two separate promises exchanged for two separate kinds of benefits. Moreover, the majority emphasised that the broader meaning of the word "consideration", as applied in the above cases in a conveyancing context, should not be extended to the current circumstances.

The minority took a more holistic view of what “consideration” moved within the composite arrangements. Looking at the EBAs and their operation together, their Honours saw SAPL’s promises (including to pay the concentrate price) as part of what induced PepsiCo/SVC to grant the essential IP rights. On that integrated view, part of the concentrate price was consideration for IP, constituting a royalty.

On the second question, both the majority and minority found that SAPL had no antecedent monetary obligation to the non-resident licensors, and that SAPL's only monetary dealings were with PBS, which invoiced SAPL and held the debt. It was also conceded by the Commissioner that the payments to PBS were held on trust or received as agent for PepsiCo/SVC. Given nothing was paid or credited to, or derived by, PepsiCo/SVC, RWT did not arise in any case.

Diverted profits tax

On the third question, the Commissioner advanced two alternative postulates: that, but for the “royalty-free” structure, the EBAs would have either expressly allocated part of the concentrate price to the IP licence, or for the concentrate price to be the price for "all the property provided by and promises made by the PepsiCo entities".

The majority considered that there were no reasonable alternative postulates, including those advanced by the Commissioner – a conclusion which turned on three critical facts their Honours described as "unique to these appeals":

The economic and commercial substance of the scheme was not for SAPL to receive "two valuable benefits" from the payments, mirroring their Honours' analysis on the question of implied royalty;

The scheme was the "product of arm's length dealings between unrelated parties"; and

The royalty-free structure adopted by the parties was a market standard and "entirely commercial" practice in the bottled beverage industry since the early 20th century.

In arriving at their conclusion, their Honours applied the standard set in Peabody: that a reasonable alternative postulate “requires more than a possibility” and must “exhibit the same substance and achieve the same results” as that of the scheme actually entered into.

The minority's perspective on DPT turned primarily on their differing view of the substance of the scheme, finding that the Commissioner did advance a reasonable alternative postulate.

Key takeaways

Although the High Court left the Full Federal Court’s result intact, the narrow 4-3 majority means the ATO is likely to maintain interest in pursuing RWT and DPT claims in commercial arrangements that are less clear than PepsiCo/SVC’s.

That said, the decision confirms the Full Federal Court’s approach to implied or embedded royalties in the RWT context. An IP licence being necessary for the business to operate does not, of itself, embed a royalty into the price for goods, and turns explicitly on what payments are made "for". However, it should be noted that their Honours in the majority were persuaded by the fact that there were two distinct contracts – one that involved IP licensing and non-monetary undertakings, and another that regulated the sale of the concentrate. Where there exists a unified contract that provides for both the sale of goods / services and licensing, avoiding the implication of a royalty may be more difficult.

On DPT, the decision upholds the high standard set by the Full Federal Court, and confirms that when the Commissioner must present a reasonable alternative postulate that corresponds to the commercial and economic substance of the actual arrangement and its non-tax results (rather than a mere re-labelling of the same payment). However, the majority decision also turned on three critical facts – and in particular, that the parties were unrelated arm's length entities – that may not be true of many multinationals.

Where the structure does align with those of PepsiCo and SAPL, we expect the ATO to lean more heavily on other enforcement measures such as transfer pricing, the general anti-avoidance rule, and hybrid mismatch and MAAL-based arguments.

The decision also highlights the importance of contemporaneous evidence to defeat a DPT counterfactual. Multinationals should be ready to explain, with documents, the robust commercial basis of their cross-border arrangements. Now would also be a good time for multinationals to review their intercompany contracts to ensure their legal effect and performance matches their intended tax character.

It is still yet to be seen how the Commissioner will reflect the decision in the finalisation of the views expressed in Draft Taxation Ruling 2024/D1 Income Tax: royalties — character of payments in respect of software and intellectual property rights and Draft Practical Compliance Guideline 2025/D4 — Low-risk payments relating to software arrangements. However, we expect changes to be made to align those views with the decision, given the expansive and purposive characterisation of payments as royalties in their current draft form.

Finally, unenacted measures to extend the general anti-avoidance rule to capture WHT-rate reductions and to extend penalties to RWT could be reframed in light of the decision. Watch for exposure drafts that try to address perceived gaps highlighted by this decision.

Get in touch